What Happens to Waste Inside Eggs? Understanding Embryonic Waste

Written on

Chapter 1: The Mystery of Waste in Eggs

When considering the life cycle of a chick, one might wonder, "How does a developing embryo manage its waste?" This question leads us to explore the fascinating world of embryonic development and waste management.

Understanding that all living beings must process energy and inevitably produce waste is crucial. This principle applies universally, even in the most extraordinary environments, such as the International Space Station.

Humans, animals, and even fetuses create waste products as they grow. Though not in the form we typically recognize, fetuses generate byproducts like carbon dioxide, urea (often referred to as fetal urine), creatinine, and bilirubin, which results from breaking down old red blood cells. In mammals, these waste products are expelled through the placenta into the mother's system for disposal.

What about eggs, though?

Section 1.1: Eggs as Self-Contained Environments

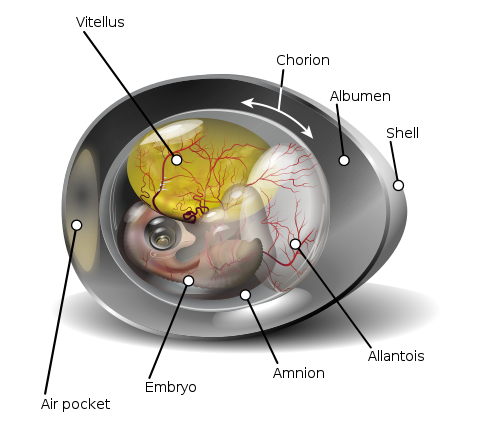

Eggs, unlike mammals, are enclosed environments that can sustain life independently if kept under the right conditions. They contain everything necessary to nurture the developing embryo.

So, how is waste managed within these eggs?

The answer lies in a specialized structure known as the allantois.

Subsection 1.1.1: The Allantois: Nature's Waste Management System

When discussing the size of eggs, it's striking to compare avian eggs, like those of chickens, to human eggs. A human egg, small enough to be nearly invisible, contrasts sharply with a chicken egg's considerable size.

Why is the chicken egg so large? It must carry all the essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals required for the embryo's growth. However, the egg does not contain an oxygen supply; instead, its shell is porous, allowing for gas exchange. This means that carbon dioxide generated by the embryo can escape while oxygen enters.

What about the solid waste produced as development progresses?

Section 1.2: Waste Management in Eggs

The developing embryo stores its waste in a unique sac called the allantois. This transparent sac fills with fluid and collects nitrogenous waste products, including ammonia (NH3).

Once the chick hatches, the allantois remains behind with the shell, as it solely serves the purpose of supporting the embryo's development. Interestingly, one reason birds, including chickens, turn their eggs is to encourage proper growth of the amnion and allantois, enabling effective gas exchange.

Chapter 2: Are We Eating Waste?

Now that we've established that embryos produce waste, the question arises: Do we consume this waste when we eat eggs?

Fortunately, the answer is no!

Most eggs consumed in Western countries are unfertilized, meaning they come from hens that haven’t mated with roosters. Without fertilization, there is no developing embryo and, consequently, no allantois. Even fertilized eggs will typically have an allantois that is either unformed or minimally developed, with no waste present.

If one were to eat a nearly hatched egg, then they might encounter a waste-filled sac, but such instances are rare and considered a delicacy in certain cultures, not commonly found in the U.S.

Wrapping It Up

In summary, embryos develop waste products that must be managed. Gases are exchanged through the porous eggshell, while solid waste is stored in the allantois, which does not form part of the chick once hatched. As a result, the eggs we consume are generally free of any waste concerns.

That's egg-cellent news!

Chapter 3: Egg Cleaning Techniques

In this informative video, discover four essential techniques for ensuring that your eggs are clean and safe to eat. Learn the secrets to preventing dirt from getting into your eggs and maintaining their freshness.

Chapter 4: The Truth About Dirty Eggs

This video addresses the common concern of dirty eggs and explains how to ensure they come out clean. Gain insights into best practices for keeping your eggs pristine and safe for consumption.