A Philosophical Portrait of Giorgio Agamben: An Interview

Written on

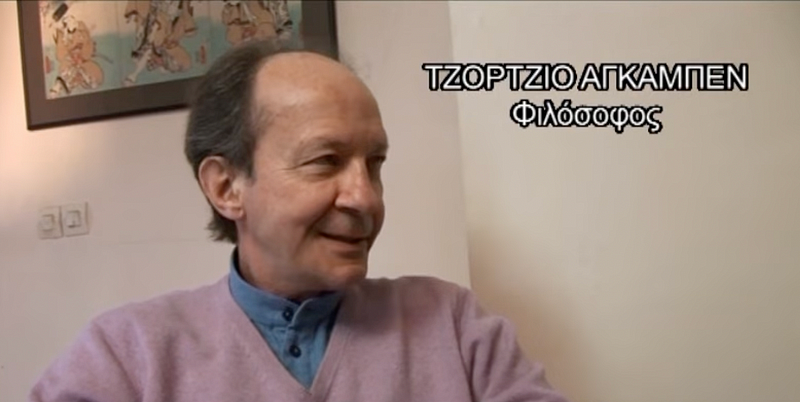

Interview with Giorgio Agamben conducted by Akis Gavrilidis. The documentary by George Keramidiotis — A philosophical portrait of Giorgio Agamben, 2013.

This is my English translation; the interview was conducted in French.

Akis Gavrilidis (A.G.) — Professor, we are creating a documentary focused on biopolitics. We sought your insights since you are a key figure in this area, originally inspired by Foucault, but with your unique perspective. You introduced concepts like the state of exception and the camp. What drew you to biopolitics, and how does your approach differ from that of Foucault and others?

Giorgio Agamben (G.A.) — Indeed, I see a strong connection between "biopolitics" and the "state of exception," which perhaps was not as explicit for Foucault. I credit Foucault for introducing the notion, but I aimed to intertwine the issues of biopolitics—where life becomes a political concern and ideology itself becomes a political stake—with the core issue of sovereignty. This led me to believe it was crucial to connect these political dilemmas with the idea of the state of exception, which, in a sense, has become a model for modernity.

In my research, I have sought to demonstrate that the state of exception, once viewed as a temporary response to emergencies, has morphed into the norm, becoming the predominant method of governance. Our political life in today’s so-called democratic societies cannot be fully understood without recognizing what Benjamin observed in 1940: the state of exception has become the standard.

This transformation began during the First World War, where states of exception were tied to wartime conditions. One cannot grasp the events in Germany during the 1930s—the rise of the Nazi regime—without recalling that Hitler, upon seizing power in 1933, immediately declared a state of exception that persisted for twelve years. The Nazi regime exemplified a prolonged state of exception, elucidating how such scenarios could unfold. Today, however, this paradigm has escalated to a global scale, where the state of exception no longer requires formal declaration; it has become an accepted state that fundamentally alters political concepts. When the state of exception becomes the norm, the frameworks of international law and human rights undergo radical shifts.

For instance, consider the concept of security, a cornerstone of contemporary Western governance, which stems from the idea of the state of exception—public safety. Foucault elucidated that this security concept emerged as a governing technique employed by physiocratic regimes just before the French Revolution, aimed at preventing famine. Their innovative approach shifted from attempting to avert famine to managing its consequences when it occurred.

It’s crucial to remember that some genuinely believe the security paradigm is designed to thwart terrorism. This belief is misguided; the reality is more about allowing catastrophes to happen, sometimes even facilitating them, so that authorities can intervene and manage the chaos. The U.S. policy over the past two decades has demonstrated this: rather than prevent crises, the strategy has often involved ensuring that they occur in specific regions to facilitate control.

Moreover, I recall the upheaval during the G8 summit in Genoa in 2001, where the police chief remarked that the government no longer aimed to maintain order but to manage disorder. This illustrates the contemporary governmental approach, which focuses on handling disorder rather than establishing order.

We observe this with the recent events in Greece, Tunisia, and Egypt, where emerging powers are aware that crises are on the horizon and seek to direct these disruptions in ways they deem necessary.

A.G. — This suggests a strategic approach, perhaps akin to Eastern martial arts? Do you perceive any correlation?

G.A. — I’m not sure if there is a direct connection, but it is certainly a possibility.

A.G. — Like karate, where you absorb the opponent's strike and then respond?

G.A. — Precisely! While it’s uncertain if that specific idea inspired them, Foucault illustrated how it had already become a governing technique with the physiocrats.

A.G. — This leads us to think about how this emergency management relates to the financial crisis. Given that Quesnay and the physiocrats were concerned with economics, does this also apply to managing financial emergencies?

G.A. — Absolutely. It’s essential to remember the original meaning of "economics." In Greek, it refers to the management of the household. Economics always revolves around management—of resources, people, and finances. It’s more about techniques of governance than mere scientific analysis. The persistent crisis has transformed into a form of management itself, becoming ingrained in our societal fabric.

In governmental paradigms today, the exception, emergency, unrest, and security are no longer viewed as anomalies; rather, they form the very core of our political mechanisms.

A.G. — How can those who are subjugated by this power strategize? Given that power allows events to unfold before managing them, what actions can we take in response?

G.A. — It’s not my role to prescribe solutions. However, I believe we must not simplistically view this as a dichotomy of disorder versus order or resistance against power, as the power dynamics we face are already calculating for resistance as a component of their strategy. While this doesn’t negate the possibility of strategy, it necessitates a more nuanced approach.

A.G. — So, it’s not about abstract laws but rather management?

G.A. — Precisely. The emphasis has shifted from law to management and measures. This signifies a significant transformation. While laws still exist, they often serve to ratify the administrative decisions made by governing bodies.

A.G. — This is a fiction of sovereignty...

G.A. — The duality persists. We shouldn’t assume that we can revert to a state governed solely by law, as the law has always allowed for exceptions. The Weimar Republic’s Article 48, which permitted the Reich President to suspend certain constitutional articles during emergencies, exemplifies this.

We cannot return from the state of exception to a purely lawful state; instead, we must work on both sides of this duality to potentially deactivate the system itself.

A.G. — We must create something new rather than seek a return to the past.

G.A. — This has been evident for nearly a century, beginning with the World Wars. The notion of returning to a healthy constitution or rule of law seems increasingly implausible. What we need is a third element. If we consider the duality of our political and philosophical frameworks—like meaning and existence, or law and exception—we must seek a third pole to transcend this binary.

A.G. — Your interest in Deleuze and Guattari is apparent. I heard you reference "Thousand Plateaus." What draws you to this work?

G.A. — I hold great admiration for Deleuze. My current research focuses on the concept of command—what it is and why it exists. Surprisingly, this topic hasn’t been extensively explored in philosophical history. While there is much discourse on obedience, understanding it necessitates examining the command itself.

Deleuze touches on this in "Thousand Plateaus," particularly in the chapter addressing language as a command. He emphasizes that language should not be viewed solely as a communicative tool but rather as a system for issuing commands. This dynamic underscores the pragmatic aspect of language.

A.G. — Thus, examining command entails looking at language rather than will?

G.A. — Typically, command has been interpreted as an act of will, but this approach merely complicates an already obscure concept. I align with Nietzsche’s view that to will is to command oneself. I suggest we interpret will through the lens of command, as the latter provides the framework for understanding the power of language.

A.G. — This leads us to the idea of anthropogenesis—when certain animals developed the capacity for speech. How does this relate to your thoughts on command?

G.A. — The emergence of language transcends mere cognitive advancements; it represents an ethical and political transformation. Unlike animals, which utilize language as one of many forms of expression, humans invest their very existence in their linguistic engagements. This is what delineates humanity and elucidates the power of language, particularly in the context of commands and oaths.

A.G. — In scientific traditions, psychoanalysis offers a framework for understanding humanity as linguistic beings. However, I notice few references to it in your work. Is this deliberate?

G.A. — Like Deleuze, I find Freud's work intriguing, but I harbor skepticism towards its underlying intentions. Psychoanalysis often seeks to control human behavior, aiming to make life manageable, whereas I believe there must be elements of life that resist control, allowing for freedom.

A.G. — You’ve suggested that in the future, humanity could engage with laws as children play with toys. Is this related to your ideas?

G.A. — Absolutely. Play exemplifies how we can deactivate and reimagine existing constructs, like weapons of war. This concept highlights the potential for transforming established uses into new possibilities.

For instance, poetry illustrates this point: it employs language not as a vessel for information but as a means to deactivate conventional linguistic functions, allowing for alternative interpretations and uses.

Listener 1: At the core, the incorporeal transformations language instigates remain connected to the body. However, can forms of command arise from non-linguistic sources, such as images or gestures? Is this part of your research?

G.A. — My focus has been on the linguistic form of command, specifically the imperative. While there are indeed other forms of command, such as gestures, they often derive from linguistic origins. This remains an open question in my research.

Listener 2: You have previously alluded to the performative force of language without fully addressing it. Might belief be a crucial term here? Belief requires an audience to manifest.

G.A. — The concept of belief also reflects the dual aspects of ontology. Today's understanding of belief tends to align with apophantic ontology—where belief equates to affirming a truth, such as a religious dogma. However, this perspective diverges from the original interpretations found in Paul’s writings, which emphasize belief as a commitment rather than mere acceptance of statements.

Listener 3: Regarding the deactivation of the ontological machine, I think of Levinas, who sought to escape ontology through the concept of the "other." What is your perspective on his approach?

G.A. — Levinas attempts to exit through ethics, which is compelling. However, he ultimately confronts pragmatic ontology, where his ideas are intertwined with a broader framework.

A.G. — To connect these abstract ideas to concrete political scenarios, how can we utilize the notion of deactivation?

G.A. — I believe the leftist movement has historically shared fundamental concepts with capitalism, such as work and productivity. This has limited its potential. We must embrace the concept of inactivity—not as mere idleness but as a form of praxis that disables existing measures. Only then can new possibilities emerge.

For instance, art serves as a modality that deactivates normative uses of language, creating alternative avenues for engagement. If we cling to capitalist concepts like productivity, we risk perpetuating the same cycles.

A.G. — In the context of undocumented migrants, the left's solidarity seems to rely on their identity as workers. Perhaps we need to rethink this approach, emphasizing inactivity instead.

G.A. — The solution does not lie in forcing undocumented individuals to adopt worker identities. Instead, we should advocate for a collective acknowledgment of undocumented status, transcending labor identities.

A.G. — Badiou insists on reclaiming the term "worker," yet you seem to lean towards a broader interpretation.

G.A. — The concept of the proletariat, as articulated by Marx, represents a non-class that seeks to challenge existing structures. Identifying a proletarian as a worker risks diluting the transformative potential inherent in the concept.

A.G. — Rancière’s perspective on the proletariat’s desire to escape classification also resonates here.

G.A. — Rancière’s ideas on the people also elude definition, which is insightful. Yet, it is vital to understand that these political challenges intertwine with theological considerations. Benjamin recognized the connection between theology and politics, which is often overlooked.

A.G. — Thank you for this enlightening discussion, Professor Agamben. We look forward to the publication of this exchange.

G.A. — Thank you for having me.