The Art of Naming: Unveiling the Secrets Behind Drug Monikers

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dreaded Disease

For centuries, one illness has instilled greater dread than smallpox, the plague, or even COVID-19: syphilis. Since its identification in the late 1400s, this affliction has left the medical community scrambling for a remedy. The first researcher to discover a cure would secure their legacy in the annals of history.

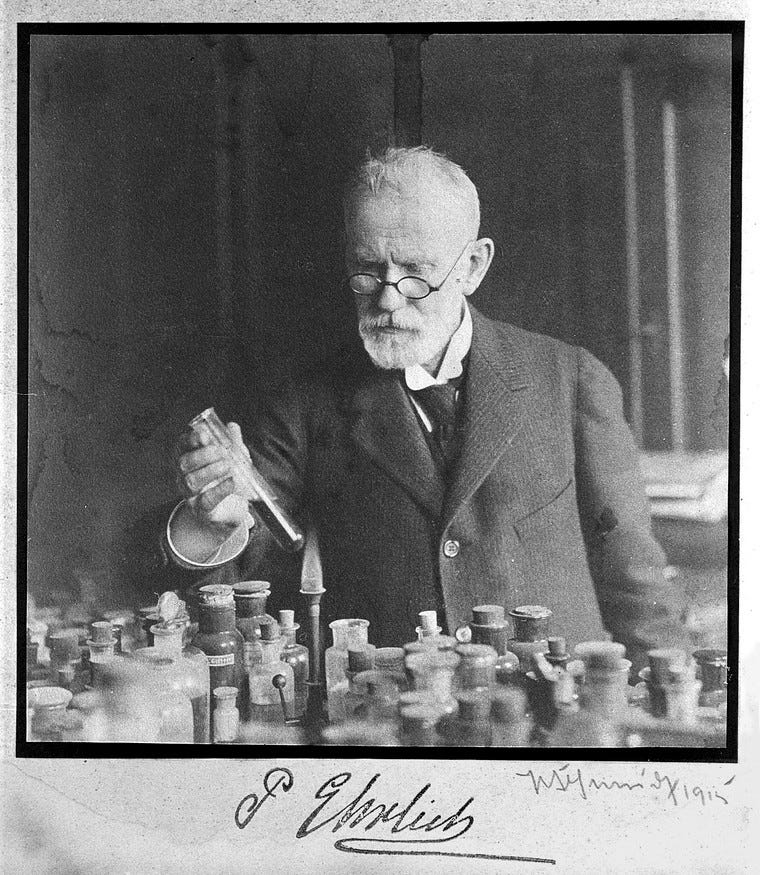

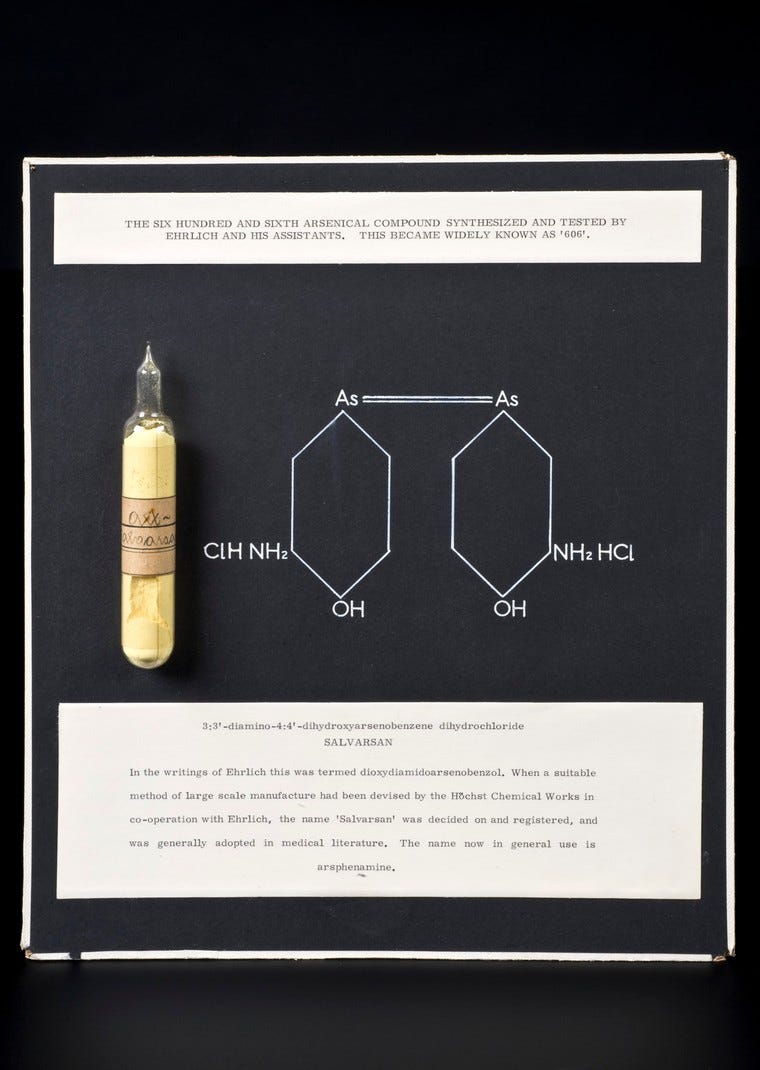

Among those in this race was German scientist Paul Ehrlich. His earlier experiments with industrial dyes had led him to organic arsenicals, which exhibited encouraging results against the syphilis-causing bacteria. However, arsenic, known for its severe toxicity, posed a significant challenge. It could lead to devastating health issues, including blindness and necrosis of limbs, ultimately resulting in death.

After refining the compound, Ehrlich created a safer alternative. He achieved success with compound number 606, but naming it proved tricky—he wanted to avoid any association with arsenic, which was widely recognized as deadly. In a brilliant marketing move, Ehrlich branded his revolutionary drug as Salvarsan, meaning "the arsenic that saves." By 1910, it was being administered in hospitals.

However, Salvarsan was still problematic. Its production was hazardous, it caused discomfort during administration, and it retained its toxicity. Ehrlich returned to his laboratory to develop a gentler version. Recognizing the established brand equity of Salvarsan, he cleverly introduced the modified product as Neosalvarsan, maintaining its legacy until penicillin emerged in the 1940s.

Chapter 2: The Naming Convention

Today, the pharmaceutical industry is a multi-billion-dollar enterprise where a drug's name can determine its success or failure. Each medication is assigned three distinct names: its structural name, the generic name, and the crucial trade name, which is patented for 17 years. The FDA ultimately decides which names are approved, following specific guidelines: names should be easy to pronounce, unique, and not imply the drug's intended use or suggest a cure.

"Pharmaceutical branding used to be an afterthought, but companies now recognize the importance of early branding and building equity in their products," states Bill Trombetta, a pharmaceutical marketing professor at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia.

The first video delves into the track-by-track exploration of NIN's "The Perfect Drug," led by its composer, shedding light on the thought processes behind the music.

A Candidate Emerges

Once a drug company identifies a potential brand name, extensive testing begins. Prescriptions are evaluated for legibility, and names are pronounced in various accents to capture regional speech variations. Surveys gauge the name's impact, and a global database check ensures no existing trademarks or unintended meanings in other languages.

This thorough vetting process can cost upwards of $2 million, just for naming.

Chapter 3: The Historical Perspective

In earlier times, the process of naming drugs was often informal, with suggestions thrown around until one resonated. Names could stem from chemical structures, discoverers, or associated institutions. A classic example is Tylenol, derived from its chemical name, acetaminophen, which has since become synonymous with pain relief.

Other clever names carry hidden meanings known only to a select few. For instance, Premarin signifies "PREgnant MARe urINe," while Vicodin cleverly highlights its potency by merging "VI" for six and "codin" from codeine.

The second video showcases Nine Inch Nails' "The Perfect Drug," providing insights into its creation and impact on audiences.

A Shift in Approach

The 1970s saw a shift toward strategic marketing, with names beginning with "A" gaining popularity to catch the attention of busy healthcare professionals. Today, in an intensely competitive landscape, drug names must evoke emotional responses and suggest improved quality of life.

Examples of such branding include Wellbutrin, Celebrex, and Claritin, each chosen to convey positive associations.

Chapter 4: Linguistic Strategies

Marketers leverage linguistic techniques to evoke specific impressions. Strong consonants like P, T, G, or D convey power, while softer sounds suggest gentleness. Names for medications aimed at women often feature soft letters and sometimes resemble feminine names, such as Velivet and Yasmin.

Conversely, products targeting men frequently employ assertive letters, with names like Levitra reflecting strength and vitality.

Future Trends

As pharmaceutical innovations advance, names are becoming increasingly complex. The next time you encounter a unique drug name, consider the marketing strategies at play and ponder whether it truly justifies its substantial price tag.