Navigating the Climate Crisis: The Intersection of Economy and Ethics

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding the Apocalypse

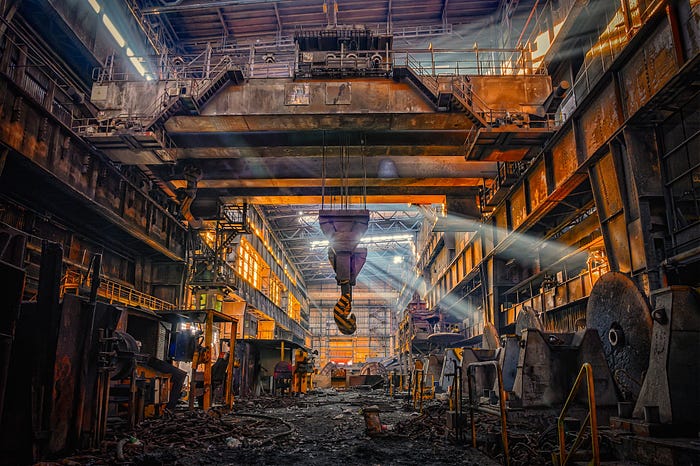

The context for addressing the climate emergency mirrors the very framework that is precipitating an environmental crisis—industrial practices.

The COP27 agreement, which aims to provide compensation to developing nations adversely affected by climate change through a global fund, further embeds climate initiatives within financial systems. Funding allocations will undergo rigorous cost-benefit assessments, competing against other social programs. Governments and global entities, like the World Bank, utilize social discount rates to evaluate the prospective costs and benefits associated with new infrastructure projects, social advancements, or clean energy investments.

This analytical approach becomes ineffective when applied to long-term climate change scenarios extending to 2050 or even 2100. Critics argue that future generations will likely be wealthier; hence, investing in initiatives today—despite their existential importance—could be viewed as a wealth transfer from current impoverished populations to future affluent ones.

Some economists and ethicists contend that we must also consider the risk of human extinction. They argue it would be tragic to implement programs aimed at benefiting humanity in the distant future, only for those individuals to face extinction due to unforeseen disasters, such as a meteor impact or nuclear conflict. This underscores the detrimental impact of utilitarian rationalism on our decision-making.

After 27 years of COP negotiations, we find ourselves in a situation where environmental exploitation has been normalized within financial markets, reflecting a moral void in contemporary society. The prevailing techno-industrial mindset appears to promote a trajectory from exploitation to dehumanization, ultimately leading to a loss of consciousness regarding our actions.

In framing the climate crisis solely as a technical issue concerning greenhouse gas emissions, we overlook its moral and conceptual dimensions. It is not merely a scientific problem but a profound crisis of awareness in our relationship with the world.

The first video, "Arcadian" - A Post Apocalyptic Coming of Age Monster Feature [Review], delves into the implications of apocalyptic narratives and their relevance in understanding our current environmental predicament.

Section 1.1: Lessons from the Industrial Revolution

Robert Allen, a Professor of Economic History, analyzed the consequences of automated weaving technology during the Industrial Revolution, a time when weaving employed a vast number of skilled workers globally. He observed that the rapid adoption of automated machines led to the displacement of skilled artisans across regions from England to China. Although some new jobs emerged to manage these machines, they required significantly less skill and were fewer in number than those lost.

The trend of mechanization soon spread to other skilled trades, contributing to a rising pool of unemployed individuals, which in turn suppressed wage levels. Before the Industrial Revolution, India and China had thriving manufacturing sectors, but they faced deindustrialization as Western economies surged. Previously, these countries exported manufactured goods; post-Industrial Revolution, they primarily supplied raw materials.

Historically, from the mid-19th century until the 1970s, a connection existed between education, productivity, and wage growth. During this period, education enabled the realization of human potential, creating a positive correlation with economic advancement. However, this relationship appears to have weakened since the 1970s, potentially due to Asia's industrial growth, which led to a reversal in trade dynamics.

The rise of mechanization has marginalized artisanal crafts, shifting the focus from quality craftsmanship to mass production of inferior goods. Artisans, who once had a vested interest in their work, have been replaced by wage laborers, resulting in a profound alienation from the products of their labor.

The moral transformation that facilitated the Industrial Revolution has also allowed commodification to infiltrate various aspects of society, turning public resources into private commodities and transforming our relationship with nature into one of exploitation.

Section 1.2: The Commodification of Nature

Currently, much of the world’s agriculture and food production has been commodified, with even freshwater resources being subject to tradable permits. The oceans face similar treatment, where exclusive fishing and drilling rights are sold off. Carbon trading has become a market for what should be a shared resource: clean air.

The commodification of agriculture has led to factory farming, resulting in the concentration of livestock and heightened risks of disease outbreaks. Additionally, the shift in how we approach food—often relying on takeout and dining out—has contributed to a decline in family meals and basic cooking skills, leading to health issues.

This commodification extends to entertainment, transforming creative expression into passive consumption, such as solitary hours on social media or video games, with detrimental social and cultural effects.

The relentless pursuit of commodification has fueled illegal activities, such as the deforestation of the Amazon for beef and soy production, underscoring a world where intrinsic value has been eclipsed by exchange value, leading to a society increasingly characterized by transactional relationships.

Chapter 2: The Economic Dilemma of Climate Solutions

The second video, Arcadia Lost Trailer, illustrates the broader themes of environmental degradation and the urgent need for sustainable practices.

Market-oriented solutions are central to contemporary environmental policies, as seen in agreements like the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. Finance plays a crucial role in combating climate change; however, the goal of climate change mitigation often conflicts with other macroeconomic objectives, including financial stability and price control.

For instance, current European monetary policies emphasize price stability and free competition, lacking provisions for significant public intervention even in the face of climate challenges. The very attitudes and values that enabled the Industrial Revolution to flourish have left us vulnerable to unchecked rationalism, rooted in the erroneous belief in continuous techno-industrial progress.

Economist William Nordhaus exemplifies this disconnect by suggesting that immediate action is not urgent, allowing for greater CO2 emissions than what would be optimal under a policy that keeps temperature increases below 2.5ºC indefinitely. His model predicts economic damages at various temperature thresholds, yet fails to account for the potential collapse of life on Earth at extreme warming levels.

The persistent belief in progress, cultivated since the Industrial Revolution, makes it difficult to imagine an end to human history, even as we face a cascade of existential environmental crises. This dissonance reveals a chasm between our current way of living and the harsh realities of our environmental situation.

The connection between capitalism and carbon emissions appears unbreakable, suggesting that pollution markets and green finance should be seen as new avenues for capitalist profit accumulation rather than effective strategies for sustainable development.

Ultimately, international climate negotiations have concentrated on carbon pricing and trading schemes, diverting attention from the necessary transition away from coal as a primary energy source. These financial solutions to climate change mask the deeper issues at play, allowing for the financialization of nature and the normalization of environmental exploitation.

The recent COP27 agreement to establish an international fund for compensating poorer nations affected by climate change further cements the connection between climate initiatives and financial markets. Funding will be subjected to cost-benefit analyses, weighed against other development projects, perpetuating a cycle where the needs of the present are subordinated to future economic forecasts.

In conclusion, the framing of the climate crisis often presumes a return to an idealized pristine state, when in fact, the planetary crises are systemic. The current terminology used to describe pollution and contamination implies that these issues are deviations from a norm that can be corrected, while in reality, they are deeply rooted in the very system driving industrial civilization.

After decades of climate negotiations, we find ourselves grappling with the normalization of environmental exploitation and the willingness to gamble with the future of generations to come, revealing the ethical void of our age. The techno-industrial paradigm continues to drive us towards a state of exploitation, objectification, and ultimately, a loss of consciousness regarding our relationship with the world.