# The World's Longest Mountain Range: A Deep Dive

Written on

Chapter 1: Mountains Beyond What Meets the Eye

While most people often think of mountains like the Himalayas, Rockies, or Andes, the longest mountain range in the world is not among them. My fascination with mountains has always been more aesthetic than scientific. Although I enjoy hiking in mountainous areas, I seldom reflect on them from a scientific perspective.

This viewpoint shifted dramatically after I delved into Bill Bryson's acclaimed 2004 book, A Short History of Nearly Everything. Bryson, known for his witty travel narratives, particularly A Walk in the Woods, takes readers on an exhilarating journey from the Big Bang to the present day, where he fondly refers to humans as "the restless apes."

In this well-researched work, Bryson skillfully narrates the evolution of physical, earth, and life sciences over the last few centuries, highlighting pivotal discoveries and the remarkable individuals behind them. For anyone curious about the world shaped by scientific inquiry, this book is essential reading.

Mountains: More Than Just Landmarks As we traverse the globe, we often rely on our eyes or photographs to appreciate mountain ranges. Recognizing mountains on relief maps, usually depicted in earthy shades, is common. Many of us can name iconic peaks and the rich mythologies surrounding them, such as Kailash, Fuji, Olympus, and Kilimanjaro. For a deeper understanding of this topic, I recommend Edwin Bernbaum's Sacred Mountains of the World.

One revelation that struck me while reading Bryson’s discussion on geology, particularly in the chapter titled “The Earth Moves,” is that mountains are not confined to land. A significant portion of the world's mountain ranges exists beneath the ocean's surface.

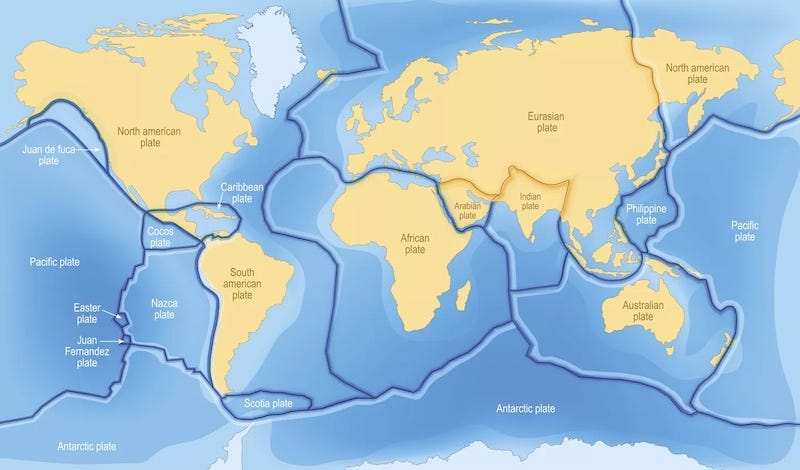

The Earth's Underwater Mountain Ranges The history of scientific discovery is truly captivating. New ideas often face skepticism and debate before gaining acceptance. The groundwork for understanding underwater mountain ranges began in 1915 when German meteorologist Alfred Wegener introduced the concept of continental drift. It took over half a century for this theory to gain traction within the scientific community.

Wegener posited that, over millennia, volcanic activity beneath the ocean floor has pushed molten rock through cracks, leading to the formation of mountain ridges on either side of these rifts. This ongoing process continuously alters the ocean floor, pushing these ridges further apart and reshaping the continents.

The Mid-Ocean Ridge, an extensive underwater mountain system, dwarfs any terrestrial range. While the Himalayas extend for about 1,500 miles and the Andes reach approximately 4,300 miles, the Mid-Ocean Ridge stretches over 40,000 miles around the globe.

This impressive network of underwater mountains can be likened to the continuous seam of a baseball. When visualized, it becomes clear how this underwater system connects various regions, extending from the North Pole through the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.

Here, some peaks rise above the ocean surface, creating islands like Iceland and the Hawaiian archipelago, each part of this vast underwater range. It's mind-boggling to realize that Mauna Kea in Hawaii, at 33,300 feet from the ocean floor, surpasses Mount Everest's elevation above sea level.

The Significance of Our Underwater Mountain Ranges This vastness makes our terrestrial existence appear small and inconsequential, even as our innate curiosity compels us to explore and understand our surroundings. For millions of years, underwater mountain ranges have existed, shaping our planet as we know it.

Yet, for much of history, our focus has remained solely on the visible mountain ranges on land. We seldom contemplate the geological movements happening beneath us, unless triggered by an earthquake.

In 1633, Galileo faced the Inquisition for asserting that the Earth orbits the sun, a view contrary to the accepted beliefs of his time. Forced to recant, he is said to have quietly remarked, “E pur si muove!” (“And still it moves!”) — a reflection of the truth that human perception does not alter the reality of nature.

This exploration into the underwater mountain ranges has illuminated my understanding of geological processes. Galileo’s assertion resonates with the grand geological movements of the Earth. Everything is in constant flux, and nothing remains static.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — In Karine’s Musings on This and That, I share reflections on personal experiences, life lessons, culture, and history. For additional essays, visit my other writings on Medium or reach out at [email protected].